JOHN KEATS (1795-1821)

LIFE AND CAREER

John Keats was an English Ramantic Lyric Poet. William Wordsworth and S.T. Coleridge belong to the first generation of Romanticists. Along with P.B. Shelley and Lord Byron, Keats was a prominent figure of the second generation of Romanticists.

John Keats was born on October 31, 1795. His father was a stable-keeper. In 1804, at the age of eight, he lost his father by a riding accident and in 1810, at the age of fifteen, his mother died. In 1811, he became an apprentice to a surgeon, Thomas Hammond, at Edmonton. During 1815-17, he continued his practice in London Hospitals but his heart was not in medicine. He felt that he was born to be a poet and soon abandoned surgery. Under the influence of Leigh Hunt, he settled down to a literary life.

The wretched circumstances of Keats life proved him the most tragic figure in the History of English Literature. In December 1818, the death of his brother Tom, broke him down badly. Isabella Jones, whom Keats loved passionately, didn’t respond to his love and soon Fanny Browne did the same. His poem Endymion was criticised badly by The Blackwood and the Quarterly Review.

Keats was suffering from consumption (Tuberculosis). His fear of death could be seen in his sonnet, “When I have fears that I may cease to be.” He died on Feb. 23, 1821. He chose his own epitaph, “Here lies one whose name was writ in water.”

FEATURES IN KEATS’ POETRY

John Keats’ poetry is characterized by sensuous imagery, hellenism, aestheticism and pictorial treatment of nature. Here are some features of his poetry.

AESTHETICISM

Keats is supposed to be the most romantic poet. He is the poet of beauty, which is external and internal both. His concept of beauty is philosophic and approach is highly imaginative. His passion for beauty constitutes his aestheticism. The famous line of Endymion, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever” strikes the key note. Poetry, in his words, should be the incarnation of beauty, not a medium for the expression of religious or social philosophy.

According to Keats:

“If poetry comes not as naturally as the leaves to a tree it had better not come at all.”

HELLENISM

The word Hellenism derives from the Greek word ‘Hellene’ meaning “Greek”. Keats was interested in Greek culture, mythology and art. Keats has no first hand knowledge of Greek literature, but he derived it from transalations of Greek classics. His sonnet On Seeing the Elgin Marbles reveals the important influence exerted on him by Greek sculpture. Ode on a Grecian Urn is the famous Ode on Greek Art.

SENSUOUSNESS

Sensuousness is the paramount quality of Keat’s poetical genius. He is the poet of senses and delight. He has catered and gratified the five human senses (touch, taste, smell, hearing and sight). He is a great lover of beauty and he gave the poetry inner touch by pictorial treatment. The Ode to Psyche contains a lovely picture of Cupid and Psyche lying in an embrace in the deep grass.

NEGATIVE CAPABILITY

Keats coined the term negative capability in a letter he wrote to his brothers George and Tom in 1817. Inspired by Shakespeare’s work, he describes it as “being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Negative here is not pejorative. Instead, it implies the ability to resist explaining away what we do not understand. His “Ode to a nightingale” and “To autumn” are full of negative capabilities.

PRINCIPAL WORKS

- ENDYMION (1818) : It is a poetic romance, which tells the story of Endymion and his quest for his dream/ideal beauty, Cynthia (Selene). Cynthia is the Godess of Moon. Keats embodies it in a rehandling of the Greek fable of Diana’s love for Endymion, a mortal shepherd, but he emphasized on Endymion’s love for Diana rather than of hers for him. The poem opens with a famous line, “A thing of beauty is a joy forever.”

- ODE TO PSYCHE (1819) : It is an exploration of the Greek godess Psyche and her association with soul and imagination. Psyche is the Greek word for soul.

- ODE TO A NIGHTINGALE (1819) : The Ode contrasts the immorality of the nightingale (as symbolised by its song) with the mortality of human beings. It also contrasts the happiness and joy of the bird with the sufferings, sorrows and afflictions of human world.

- ODE ON INDOLENCE (1819) : In this Ode, Keats affirms that neither love, ambition nor poetry has charm enough to tempt him from a mood of exquisite somnolence or indolence.

- ODE ON MELANCHOLY (1819) : Keats explored the complex emotion of melancholy and advised the reader, how to confront and appreciate it’s presence.

- ODE ON A GRECIAN URN (1819)

- ISABELLA : It is a tragic narrative poem.

- ODE TO AUTUMN (1819) : The poem is a perfect Nature Lyric. No human sentiment finds expression; only the beauty and bounty of Nature during autumn are described.

- LA BELLE DAME SANS MERCI (1819) : It is a ballad, that tells the haunting story of a Knight who falls under the spell of a beautiful and mysterious lady.

- HYPERION (1818-1819): It is fragment, an incomplete epic poem that he started writing when he was nursing his brother. It is about the war between the Titans and the Olympians, the dethronement of Hyperion, the old Sun god, by Appolo, the new. It is modeled on Milton’s Paradise Lost.

- LAMIA : The narrative poem in heroic couplet. It is a story of a serpent woman who loves a young Corinthian. Keats borrowed its story from Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).

ODE ON A GRECIAN URN

TEXT

Thou still unravish'd bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fring'd legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear'd,

Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone:

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unwearied,

For ever piping songs for ever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

For ever warm and still to be enjoy'd,

For ever panting, and for ever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy'd,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty,—that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know."

INTRODUCTION

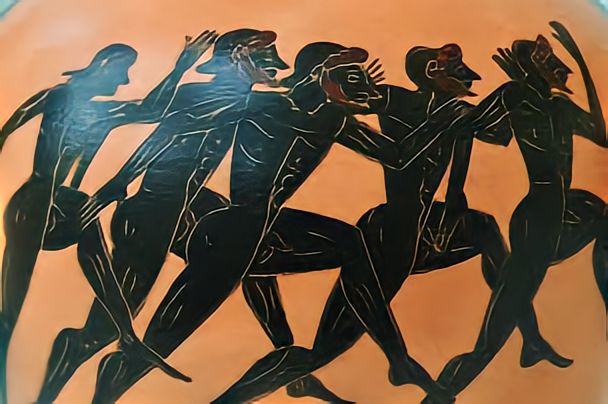

Ode on a Grecian Urn was written in May, 1819. It was published anonymously in the 15th edition of a journal “Annals of Fine Arts” in 1920. The edition includes several great odes of 1819, i.e. Ode on Indolence, Ode on Melancholy, Ode to a Nightingale, Ode to Psyche and Ode on a Grecian Urn. The poem Ode on a Grecian Urn is an Ekphrasis (to express the art in sensuous words). Keats had a natural affinity with the Greek literature and art. The Greeks used to cremate the deads and deposit their ashes in an Urn (generally made of Clay, metal or marble) and decorate the outer surface with carving day life sceneries.

There are many perspectives regarding the source of this poem. It is believed that Keats was inspired to write this ode after reading two articles by Benjamin Haydon (english artist and writer), but critics like Colvin point out that ‘no single work of antiquity can be regarded as the source of inspiration’. In 1812, Lord Elgin pillaged a collection of ancient sculptured marbles from Athens and deposed them in the British Museum. The sonnet, “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles” by Keats prove that one source was not sufficient for inspiration. Keats saw and read the Greek literature and a beautiful Grecian Urn, inspired this beautiful poem.

THEME OF THE POEM

Keats addresses the Urn, a symbol of timelessness, permanence and aesthetic beauty and contrasts it’s eternity and beauty with the harshness of mortal life. The eternity of art is contrasted with the mortality of reality. The Urn gives its final lesson: “beauty is truth, truth beauty, that is all you know on earth and all you need to know”.

VOCABULARY

- Unravish’d : Untouched, virgin

- Foster child : a child raised by someone who is not its biological parent

- Sylvan : of, relating to, or inhabiting the woods

- Deities : divine character or nature

- Tempe and Arcady : vales of Greece

- Pursuit : an effort to secure or attain; quest

- Ecstasy : a state of sudden, intense feeling

- Adieu : goodbye; farewell

- Passion : strong feelings

- Cloy’d : disgust or sicken with an excess of sweetness, richness, or sentiment

- Parching : something hot, dry, or thirsty

- Alter : a high place that is the centre of a religious ceremony

- Flank : the side of an animal’s body

- Citadel : a castle on high ground in or near a city where people could go when the city was being attacked

- Pious : having or showing a deep belief in religion

- Desolate : emptied, isolated

- Overwrought : carved

- Tread : to press down on something with your foot

EXPLANATION

STANZA 1

The poet sees a Grecian Urn (not really) and the human activities carved upon it. The life like figures on the Urn astonished him. In the first stanza Keats emphasises the silence of the Urn, using metaphors – an “unravish’d bride of quietness” and a “foster child of slow time and silence”. The mental and emotional attitude of the poet is exquisitely reflected in the clear cut, yet suggestive, phraseology of the first two lines. The Urn is untouched and kept with safety. The Urn is fostered or nourished by time.

The images on the Urn depict a rustic scene and the scenes depicted on it tell us the story, therefore the urn is Sylvan Historian, who can dictate the history better than a writter or poet. Poet wonders whether the legend, searching something in the vales of Tempe or Arcadia (Switzerland) is mortal or some divine character.

Poet introduces the mystery of the scenes by rhetoric questions and gives us some idea, that there are maidens who are being chased by their lovers. They are struggling to escape. This is followed by the picture of the musicians producing joyous strains of music.

Note : The word “shape” in line five, not only draws the attention to the outlines of the Urn, but it also suggests the lines and curves of the feminine body, as already conveyed as “unravished bride”, says Charles Patterson.

STANZA 2

In the second stanza, the speaker sees the figures as mentioned in the first stanza more keenly. The musician plays on his pipes. The poet says that the music that we hear in reality is “sweet”, indeed, yet the music that we imagine is “sweeter.” It appeals to the spirit whereas the heard warbles appeal to the voluptuous senses only. The melodies displayed on the urn can not be heard but the speaker considers that the unheard music is more perfect in its abstract and immortal form. These carvings make the poet conscious of the superiority of art over nature. The music which is imagined is importantly sweeter than the the music which is actually heard.

The fair youth on the Urn is fortunate. He’ll always sing his songs. The trees, in their eternalized image, can never be bare, The autumn cannot shed their leaves. The lover carved on urn can never kiss his beloved but the poet suggests him not to grieve because his beloved will never fade, she will be beautiful and loyal always. And the maidens trying to escape will neither escape nor will be catched. Because they are now not in real life, they are immortalized by art.

STANZA 3

In the third stanza, the speaker praises the trees which can noway lose their leaves. This “nature” on the urn should be happy to never face the seasonal Cycles. The musician of the unheard songs should likewise be happy in this immortal and frozen state. His songs will never be monotonous. He’ll always be piping songs. His songs will not lose their charm. He’ll not be tired of them.

The poet all of unforeseen turns to the image of the lovers. The love of the world of urn is full of passion. It’s ever panting and ever youthful. He thinks that this immortal, unchanging state isn’t conducive to happiness for those who live in time. The tone turns from happiness to sorrowfulness. The ejaculations only allude at his own unfulfillment of love. “All breathing mortal passion” is different as this leaves a heart heart high- rueful and cloy’d.

In this stanza Keats is led to the contemplation that the trees sculpted will never exfoliate their leaves, nor the musician ever sick of his songs, nor the love of the youthful people ever decline. The joy of art is eternal and is far more satisfying than the mannas of real life which end in a sad malnutrition.

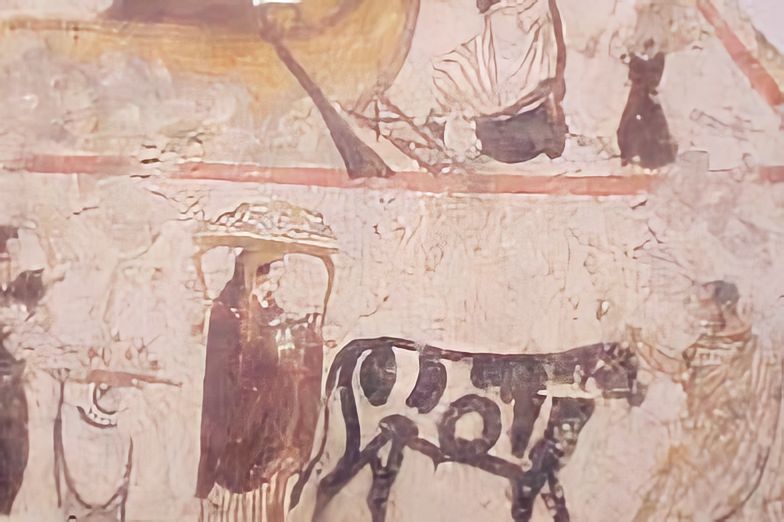

STANZA 4

This stanza, describes the scene of sacrifice, that were common feature of Greek religious ceremonies. The procession is headed bya priest who leads a young calf to the place of sacrifice. It seems that the calf, with half open mouth, prays with its head up raised. The heifer is decorated with garlands of flowers. The priest is called “mysterious” because nothing is known or his identity of religion.

The town seems to be situated close to a river or on a sea shore or at the feet of a hill on the top of which stands a fortress. It is morning time, the town is empty because the people going to the sacrificial place, will never be back. The scene is carved on the urn and thus now there can be no movement. There is no one in the town who could tell why the town is empty or desolate.

STANZA 5

As the urn is Greek, the poet addresses it as “attic shape” and “fair attitude” to convey the beauty. The idea is that, when we gaze at the urn we get into a mood in which all speculations seem futile. The urn teases us with its beauty and eternity. It is cold because it is made of marble, have no life, and pastoral because scenes are rural. Poet says that ages after ages, our generations will come and go but the urn will remain as it is. It will convey the message to generations: that Beauty is truth, truth beauty. Beauty and truth are the same things, what we imagine is beautiful and what we live in is illusion. The urn is a friend to man as it conveys the theme of the poem. Thus the immortality of art and mystry is the only truth.

STRUCTURE OF THE POEM

The poem is written in five stanzas, with ten lines each, beginning with a Shakespearean quartrain with rhyme scheme ABAB and ending with a Miltonic sestet with rhyme scheme CDEDCE (stanza 1st and 5th), CDECED (stanza 2nd) and CDECDE (stanza 3rd and 4th). Each stanza is written in iambic pentameter lines.

In stanza one and five the Urn is addressed. In stanza two, piper, fair youth and bold lover are addressed. In stanza three, Happy boughs, Melodist and love/lover are addressed. In stanza four, priest and little town are addressed.

FIGURES OF SPEECH

- The poem open with an apostrophe, addressing the Urn.

- Metaphors in “unravish’d bride”, “foster child”, “Sylvan historian”.

- Personification in “Unravish’d bride”, “foster child”, “thou silent form”, “true friend to man” and “thou sayst,……..”.

- Assonance in “Thou foster child of Slow time and Silence”.

- Paradox in “foster child of silence”, “unheard melodies” and “ditties of no tune”.

- Pun in “Fade- loosing beauty and going away” and “Fair- faithful and beautiful “.

- Synecdoche in “a heart”, “a burning forehead” and “parching tongue”.

Sir, sari poetry ka dalo na ….plz

Very nice sir ji

Very good

Please update all the poems 🤗😍